John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts, Washington, DC

May 4, 2008

The National Symphony Orchestra Conducted by JOHN WILLIAMS

With Hosts Martin Scorsese and Steven Spielberg

The 2008 Kennedy Center Spring Gala: ‘The Art of Film Music’

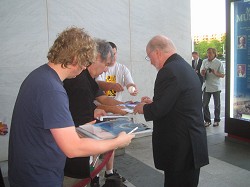

PICTURES (Before the concert)

JWFan Jack H. Lee managed to take a few pictures of John Williams outside the Kennedy Center, right before his latest concert in Washington, DC. The Maestro conducted the National Symphony Orchestra on Sunday, May 4, in an event hosted by Martin Scorsese and Steven Spielberg.

WASHINGTON — “The Art of Film Music” was the featured entertainment at Sunday’s Kennedy Center Spring Gala, the second-biggest annual fund-raiser next to its high-profile Kennedy Center Honors, that drew $2.7 million. As usual, the KenCen goes straight to the principal sources.

With composer John Williams conducting the Center’s own National Symphony Orchestra, and directors Martin Scorsese and Steven Spielberg playing hosts, the three past Kennedy Center honorees treated guests, including Tom Cruise and Katie Holmes, to an evening of film scores and inside perspectives.

Carefully-edited scenes from Jaws, E.T., Close Encounters of the Third Kind and other Spielberg-Williams collaborations played onscreen as the orchestra performed the film’s music.

NSO music director Leonard Slatkin conducted the finale, a rousing tribute to Raiders of the Lost Ark.

Hard to top Sunday’s Kennedy Center Spring Gala. The $2.7 million party boasted Steven Spielberg, Martin Scorsese and John Williams– all Oscar winners and recipients of the center’s Honors — for a salute to movie music. The three presented a crowd-pleasing mix of clips (Lawrence of Arabia, Doctor Zhivago, Jaws, Indiana Jones, E.T.), commentary and film scores. Williams got the night’s biggest laugh by repeating his favorite Spielberg line: “I said, ‘Steven, you really need a better composer than I am.’ He said, ‘I know, but they’re all dead.’ ” Ba-da boom.

Put film directors Steven Spielberg and Martin Scorsese in a room together with composer-conductor John Williams and add a fleeting glimpse of Tom Cruise with wife Katie Holmes, and it’s Hollywood on the Potomac all over again. That was the scene Sunday at the Kennedy Center Spring Gala, celebrating “The Art of Film Music,” a formal dinner and concert to raise more than $2.7 million for the institution’s coffers.

Donating their services for the occasion, a solemn Mr. Scorsese and a jaunty Mr. Spielberg acted as hosts to introduce familiar themes from well-known films, played by the National Symphony Orchestra under Mr. Williams’ direction along with the NSO’s outgoing music director, Leonard Slatkin.

The evening ranked as a love-in among the talented crew, frequent collaborators and Academy Award winners through the years. “I can direct bicycles to fly, but music really makes them soar,” Mr. Spielberg said of Mr. Williams’ Oscar-winning score for E.T.: The Extra-Terrestrial from 1982.

Miss Holmes and Mr. Cruise — he is a good friend of Mr. Spielberg’s and has appeared in films for him and Mr. Scorsese — were merely spectators, ushered in and out of the Concert Hall as though they were Fort Knox gold.

Concert Review by Jack H. Lee

This was my seventh time to see John Williams. It never really gets tiring (well, maybe just a little!). So while there was sufficient “been there, done that” for me in terms of the program, jokes, and various highlights, seeing the master live is a tremendous privilege. But what made the program especially thrilling was to see two directors I’ve always admired: Martin Scorsese and Steven Spielberg.

The announcer first introduced conductor Leonard Slatkin, who is in his final season with the National Symphony. Slatkin walked only halfway toward the center and stood at a podium. He quipped that normally he would go all the way to the conductor’s platform, but because of the occasion, he would yield it tonight. He briefly talked about how Beethoven composed the most five recognizable notes ever written and hummed the beginning of the Fifth Symphony. Then he added how John Williams beat that with his two note motifs from Jaws, and hummed that. Slatkin also recounted how Leonard Bernstein once referred to Aaron Copland as the very best we have. He slyly noted that Aaron Copland has been dead for a long time now, and said he now wanted to introduce “the very best.” With that, Williams took to the stage to thunderous applause.

The first half of the program, “A Tribute to David Lean” was introduced by Martin Scorsese. Usually, Scorsese is the type that likes to discuss the types of movies he grew up on and how they affected his film making style. But he said very little on the matter. He gave various overviews on the composers Lean worked with and the different, memorable music written for it. He mentioned various trivia, like how the best-known piece from ‘A Bridge on the River Kwai’ (“Colonel Bogey’s March”) was actually adapted from an old military march, or how ‘Dr. Zhivago’ gave us one of the iconic love themes (“Somewhere My Love,” a.k.a.“Lara’s Theme”) of the day. When he mentioned the song was so popular that everyone “from Johnny Mathis to Roy Clark” was recording it, people found that amusing upon mention of Clark’s name. Williams led the NSO after each introduction, with the music playing to a montage of key scenes from their respective films, which also included ‘Blithe Spirit,’ ‘A Passage to India,’ ‘Oliver Twist,’ and ‘Lawrence of Arabia.’ Everything was played with great dignity, showcasing either dramatic moments or the superb cinematography common in Lean’s films.

In the second half of the show, Williams did a slight variation of his “you need a better composer than I am” anecdote (in which Spielberg would say “They’re all dead”). Usually this joke appears whenever the piece from ‘Schindler’s List’ is about to be performed. Instead, Williams applied this joke as an introduction to Spielberg. Williams briefly discussed his longtime collaboration with Spielberg. Williams said he would jokingly ask Spielberg why he was still sought out for a film when there were better composers out there. And that was when Williams added Spielberg’s now famous punch line.

Excerpts from Close Encounters of the Third Kind were performed next and well received. However since those famous five notes aren’t really heard full blown until toward the end, for those who weren’t familiar with this particular piece, it may not have been as accessible right away. With all its dissonance, it’s a longer build up (just like in the film) to get to the theme music, whereas with many of his other, tonal compositions, the melody is heard almost right away. My wish is that someday a concertized adaptation of the conversation music be performed, because you just know that’s what people remember most of those five notes!

When Spielberg introduced the music to Jaws, he said how difficult it was to film, largely due to the problems with a mechanical shark that always sank. He said two things saved the film. The first was the faith in the audience. By giving them the impression there was a shark present (when it wasn’t visible) added a layer of terror. The second thing that greatly aided the film was Williams’ music, which Spielberg said must have been responsible for people being afraid to go even into a wading pool. In the thirty-plus years since those two-notes terrorized audiences, the ‘Jaws’ motif almost seems to be a parody on itself today. After Williams gave the downbeat and the ominous strains of the main theme started, audiences laughed, as if hearing an old, but effective joke. (A similar incident also happened when Erich Kunzel conducted this piece here last fall.) Williams then proceeded with the medley “Out to Sea/Shark Cage Fugue,” with its delightful maritime theme for the Orca, coupled with the tense adventure music of the impending confrontation with the shark.

When I saw Williams at the Kennedy Center in 2003 (1/24/03), he explained the technical aspects of spotting a film, utilizing the early scenes of young Indiana Jones as an example of how the music would be placed. It was a “before” and “after” run-through to give the audience an idea of how greatly music affects a movie. Back then, the set up was a little more elaborate since the orchestra used click tracks and Williams had a time encoded work print as if they were doing a real recording. This time, however, Spielberg did the spotting. He introduced the segment as being “from the third but not last” Indiana Jones film, which brought a loud ovation. There were a couple of humorous moments. After Spielberg explained there would be only dialog and sound effects, we were greeted with a black screen. He then joked, “and then we have to turn it on!” Apparently someone in the control booth was having trouble operating the A/V equipment, since a pop-up menu panel (displaying the video options), then appeared that blocked off most of the picture. Spielberg had fun with the audience by pleading, “I didn’t film that panel!” After a few more moments, the problem was corrected. As the footage played, he said where Williams would “catch” certain pieces of action, how a heroic piece would come in here and there, and how many little segments have to be written for the ever-changing pace. Another joke Spielberg threw in was that if this movie had been made in France, it would play exactly like this (e.g., without any music). The performance was fine, maybe a little off here and there in terms of timing, but that’s to be expected under the circumstance. The ever changing dynamics gives you an appreciation of how finely detailed and crafted Williams approaches his work. The only complaint I had was that the music drowned out the rest of the movie.

Spielberg recounted of all his work with Williams, Schindler’s List was the most emotional and gratifying of them all. Whether if it was out of respect or other reasons, this was the only time Spielberg left the stage during the performance to give the spotlight to Williams and concertmaster Nurit Bar-Josef. It’s hard to put into words how effective and moving this work is on so many levels, but when you hear it live and under the baton of Williams, it’s just so special. It was stunningly beautiful and continues to be. Ms. Bar-Josef had previously performed this in Williams’ 2003 concert and just like back then, you could sense the audience getting emotional with every note and subtle nuance.

The finale was another fan favorite, the climax from E.T., played to the film (the scene where the kids rescue E.T. so he can rendezvous with the mothership). The audience cheered enthusiastically the moment the bicycles took flight and again when E.T.’s ship launched into the heavens. Again, the music was louder than the rest of the movie, but it really didn’t matter. People loved the music and just let it narrate the movie.

There were three encores. Spielberg reminisced how they began with The Sugarland Express. Admittedly, this was somewhat “new” to me in that it’s the only Spielberg/Williams collaboration I’m least familiar with. So without any point of reference or visuals to go with it , I wasn’t entirely too sure what I was listening to. I’m vaguely familiar with the Boston Pops arrangement, but without the harmonica accompaniment, I felt a little stumped by the piece, even with Williams’ melodic trademark all over it. That didn’t stop me or the audience from enjoying it any less. It showcased some of the many faceted styles from Williams’ oeuvre and just as appreciated. Next up was “Flight to Neverland” from Hook, another crowd pleaser with its magical, fairytale feel. What’s interesting is – at least in my experience with Williams concerts – is that just mentioning the name of the movie will generate an immediate response of familiarity.

For the final encore Williams suggested to doing some Indiana Jones music, but letting Leonard Slatkin conduct. With that, Slatkin took to the podium. With the new Indiana Jones film just around the corner, the audience roared with approval the moment “The Raiders March” began. Spielberg and Williams cheerfully stood side-by-side like old army buddies as Slatkin led the NSO with gusto to a rousing finish. After the conclusion, there was the proverbial standing ovations and curtain calls. Williams, ever the humble professional that he is, pointed to various members and sections of the orchestra, as if thankingthem for the music. It ended a terrific, star-studded night on a high note.

— Jack H. Lee