Meet Astronaut, Musician, and John Williams Fan Sarah Gillis

By Karim Elmahmoudi

September 26, 2024

Astronaut Sarah Gillis performing John Williams’s “Rey’s Theme” while in orbit aboard Polaris Dawn

Astronaut Sarah Gillis just returned from a groundbreaking mission where she and crewmate Anna Menon made history as the furthest women have ever been from Earth. Her journey not only pushed the boundaries of human exploration but also brought a unique piece of Earth’s culture into space. Sarah famously played the iconic music of John Williams while orbiting far above the planet, setting another new record for the furthest as-live musical performance from Earth. Her achievements mark a new era in space travel, blending scientific discovery with the arts in a way that resonates with both aspiring astronauts and music enthusiasts alike.

As Mission Specialist for the Polaris Dawn mission, Sarah and crew launched on September 10, 2024, and returned five days later, successfully completing all mission objectives. Notably, the crew reached an altitude of 870 miles above Earth – the furthest any human has been since Apollo 17 returned from the moon in 1972. Joining Sarah on this historic mission were Mission Commander Jared Isaacman, Pilot Scott Poteet, and Mission Specialist Anna Menon. During the mission, Sarah and Jared Isaacman also tested the first commercial space suits designed and built by SpaceX, resulting in Sarah becoming the youngest person to ever walk in space.

Just eleven days after her return to earth, I was eager to speak with Sarah about her experience in space, performing “Rey’s Theme” from orbit, meeting John Williams, and her remarkable journey as a musician, rocket scientist, astronaut, and history maker.

KE: How and when did you first fall in love with the violin, and what drew you to this particular instrument?

SG: Gosh! That goes really back to my mother. My mom was a professional violinist. She studied violin in school and was a teacher for many years, and played in the Boulder Philharmonic Orchestra eventually running the orchestra. But she really is the one that picked violin for me and my sister. We started at a very, very young age, and I would say I started learning just through osmosis from following my sister around age 2, and just watching her. It’s been a lifelong journey of learning and being part of the world of music and made a lot of sense to tie that into my mission. I come from a musical family. My grandmother was a piano teacher as well, so goes back a long time.

KE: Who has been the most influential person in shaping your musical performance style?

SG: That’s a good question. I feel as if it’s probably Dr. William Starr, who was my teacher after my mom. I started taking lessons with Dr. William Starr in high school, who was one of the founding members of the Suzuki Method (an influential mid-20th century violin teaching approach in the United States).

He traveled to Japan in the 60’s with his whole family, and is fairly central to bringing that movement to the United States. He was just an incredible violinist. He gave incredible attention to learning music, and being able to teach how to learn music. I would say he had a very large influence in my performance style overall.

KE: What was the defining moment in your journey as a violinist?

SG: What’s so interesting is my journey as a violinist has been up and down over time. I actually didn’t intend to pursue violin. I basically stopped playing when I graduated high school beyond casual violin playing. You know, string quartets or ensembles stuff like that. I really chose this different path of engineering, which was extremely hard for my brain at the time. It was a whole new way of thinking and problem solving in a new language I had to learn. But it really turns out it does all stem from a common source where the skills I learned tackling music and learning music actually, probably directly benefit my engineering brain.

And it actually wasn’t really until we started talking about this mission that kind of came back out of the closet as something that I wanted to share with the world. And so, although it is a small moment in the journey that has been my violin playing, I feel the moment we brought that orchestra together, and were able to work with John Williams and having him come to this performance and be bought into this vision, was one of the most defining moments in this journey.

I don’t think there’s anything more special than creating something so much larger than yourself.

KE: I’ve seen musicians with daily routines that incorporate everything from performance practice to fitness to mental preparation. Do you have a daily routine that you do? And how did you manage it? Especially with the demands of your space training?

SG: I would say routine is something I have tried to accomplish over the last two and a half years, and something I never mastered. We have been in so many different places, doing so many different things every single day that I think the only normalcy is that it was never normal and never consistent.

But I would say I always tried to find time to certainly exercise, staying healthy and keeping your mind active.

And then, wherever I could, I would try to bring a violin. I would say that often added stress for me, because I have a violin that I absolutely love, and we were traveling all over the place, and I don’t have the ability to keep it in perfect humidity and temperature control, and all of that. But wherever I could bring it, and I felt it was going to be safe, I’d bring it, and then I’d have time to practice and just play with the music. I always came back to it when things were super stressful, and I would just go, and I would play, and it would immediately calm my mind and my nerves. Especially in the pre-launch week, I would say, where we were in quarantine. There were super-fast paced schedules when we first arrived at the Cape [Canaveral]. Just go, go, go, and then I just had these moments of serenity when I’d go, and I’d practice, and it was absolute calm. Nothing else mattered. And that was really grounding and focusing for me.

KE: So how did you become a fan of John Williams? What was your first introduction to his music?

SG: That’s a great question. I actually don’t know what the very first introduction was. My guess is it was through Star Wars the Phantom Menace. My brother was very particular about what order I was introduced to the movies.

And I would have to ask him which route he took me if it was release order, or I think he took me through story order. We wanted to go through the series of emotions that you’d have if you were actually watching them as they came out. He’s an immense Star Wars fan, and so was kind of introducing his kid sister years after he had discovered it was a joy for him.

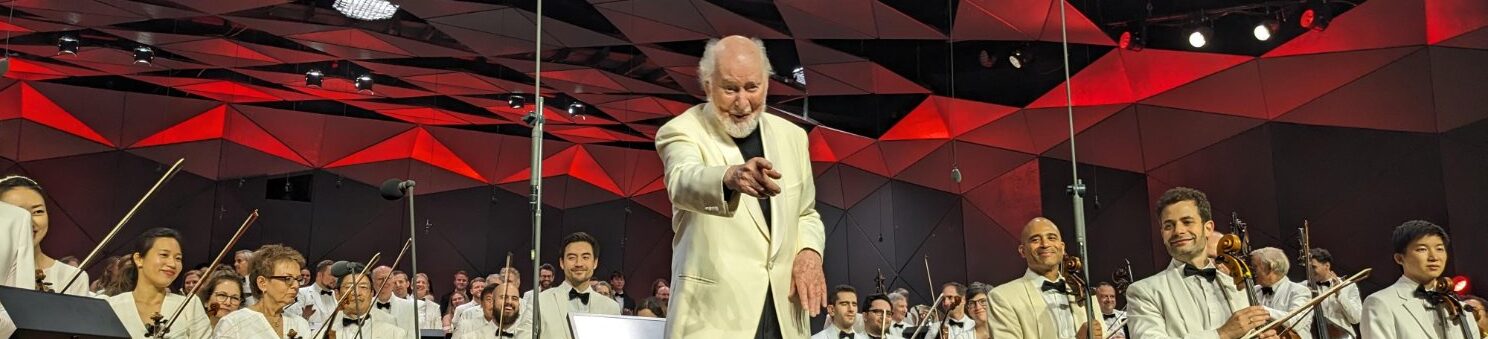

John Williams talking to Sarah Gillis during the performance rehearsal of Williams’ “Rey’s Theme” from Star Wars: The Force Awakens.

KE: Is this the only John Williams piece that you’ve performed?

SG: I have certainly played some of his other music, nothing that’s been public or shared but what my sister and I really love, just kind of riffing and improvising with each other. And so, we’ll just pick a random song and play it, create harmonies and riff off each other, which is really fun. And I feel we have, probably played other music of his.

KE: What about John Williams’s music resonates most with you as a violinist and as a fan?

SG: I think what resonates most with me is his ability to bring a universe and a world to life. If you were to watch those movies with just the footage without the soundtrack that he has written is just not the same. It’s not this immersive world that has emotion and nuance and color in a way that is absent without it. And so, I really feel as if those movies would not be what they are without the soundtrack that accompanies them. And that’s a hundred percent a tribute to John Williams and his brilliance in music.

KE: How did you choose Rey’s theme to perform in space? Was there a specific reason behind that selection?

SG: You know it kind of felt like fate. By the time I actually went to pick it, I spent a long time listening to violin music. Going through song after song after song, thinking “what would I want to share with the world?” One of my all-time favorite violinists is Anne-Sophie Mutter. And so, I was listening to a lot of her music along with some of the other greats, and just trying to get inspiration. I came across her performance of this version of Rey’s Theme. John Williams did write this version for her and man was it stunning! It was beautiful! It was Star Wars that I absolutely love. Rey is actually one of my favorite characters. I know that could be controversial, but she truly is, and I think that’s really because I was so excited to see a character in the new movies that I could relate to that seemed human. That was a girl that was doing really fun technical things. Working with machines and just having the skill set that she could do anything. She seemed to be able to learn anything immediately, and I thought, “this is awesome! I want to be like her.” I feel she was the first character that inspired a lot of little girls to actually be interested in Star Wars and to be interested in that universe. It was awesome discovering this incredible piece of John Williams’s music, that is her theme song.

The beautiful playing of Anne-Sophie Mutter, who I was just so inspired to hear, and then also that it happened to be Rey’s Theme. It all kind of came together, that it was exactly the right piece. Then, we just needed to figure out whether or not I could play it, and how to make that work logistically.

KE: Did you consider the possibility of commissioning a brand-new piece from John Williams especially for this flight? Something like a “Polaris Dawn Overture” for violin and orchestra?

SG: That would have been so cool. We did talk about commissioning music at some point. What’s really interesting about this mission is because it was a development mission, we were never more than a year out from our launch date. Even though that was two and a half years later that we actually launched. As we were going through the process, there was no time to have something written. In hindsight, we would have had the time but we were always only six months to a year from launch but for a really long time, and that really limited the ability to have something written just for the mission itself. Something to think about for a “sequel” flight.

KE: Please tell us about the unique challenges of involving multiple orchestras across the world in this project?

SG: We had the opportunity to test out the Starlink Internet Constellation talking to SpaceX Dragon and providing internet to the spacecraft for the first time. This was one of the big technical objectives of our mission. We recognized that this is in some ways similar to the first time you have, say, radio shared around the world, or somebody hears a radio broadcast. It is important to send a message over that that is impactful, that is meaningful.

As we were talking about ideas for what we could do there, we quickly settled on music. The universal nature of that language and what you can do through music to connect the world and through this technology. If you can provide connectivity around the world supporting access to telemedicine and to education, you can truly transform our world and people’s lives in a very tangible way.

We started thinking about ways that we could engage maybe with orchestras around the world. Thinking about networks that are working with kids around the world. Specifically, that’s super important to me to inspire new ideas and different paths that kids might not know were even possible.

We got in touch with El Sistema U.S.A., who is a partner organization to the El Sistema groups all around the world and started working with them on a number of pieces. One was an educational curriculum that I really wanted to provide some ideas for kids of both space themes and music themes, bringing together something that feels unique to me.

Just illustrating what is possible and maybe what some career options are in both the music and science fields so wanted to create educational resources that kids could engage with in the classroom. We also wanted to work with some of these groups and include them in this video message from space. We worked with El Sistema to figure out what groups might be interested and where they were located around the world trying to engage a large assortment of people. It was a really fun process to work with El Systema U.S.A and all the student groups. It was really kind of an organic creation. All of this came together in an incredible way that I don’t think I could have envisioned at the start of all this but it was extremely meaningful to me to be able to share this with so many, particularly students around the world.

As a child, I couldn’t have envisioned something as big as this, or as absolutely wild as this, and to be able to show kids globally what’s possible is extremely profound to me.

KE: What was it like collaborating with John Williams? How much direct interaction did you have and how did that impact your performance?

SG: So, in order to actually do this, we obviously needed to get his permission to use his incredible music. We did have a team that knows him and was able to reach out and contact him. Oh, and he was extremely excited! He thought this was such a lovely idea which is absolutely surreal. We also needed to get Anne-Sophie Mutter’s support for this because she actually has the rights to the violin arrangement of this in particular. John reached out to her, asking for permission to do this as well.

It needed all of the right people to say yes, and they were all extremely excited about the idea! That was really inspiring.

I think it was extraordinarily stressful when I found out that John Williams actually wanted to come to the recording session, maybe a week in advance, and so going from not being a professional, practiced musician for maybe a decade of time, and stepping into this was not the least stressful moment of my life. But when he showed up at the studio he was so kind and so supportive in a way that just completely put me at ease, and it was so cool to see him working with Jeri Lynne Johnson, the conductor. She had some questions about the score, and he was talking her through different parts of it. I think all of the musicians were also just so excited, kind, and enthusiastic about what we were doing. It was such a cool moment in time to be bringing together the Master of space music and creating something that’s actually going to go to space, and also with music we all love, aware of what it can do to transform lives. So, it was a very, very special moment for me.

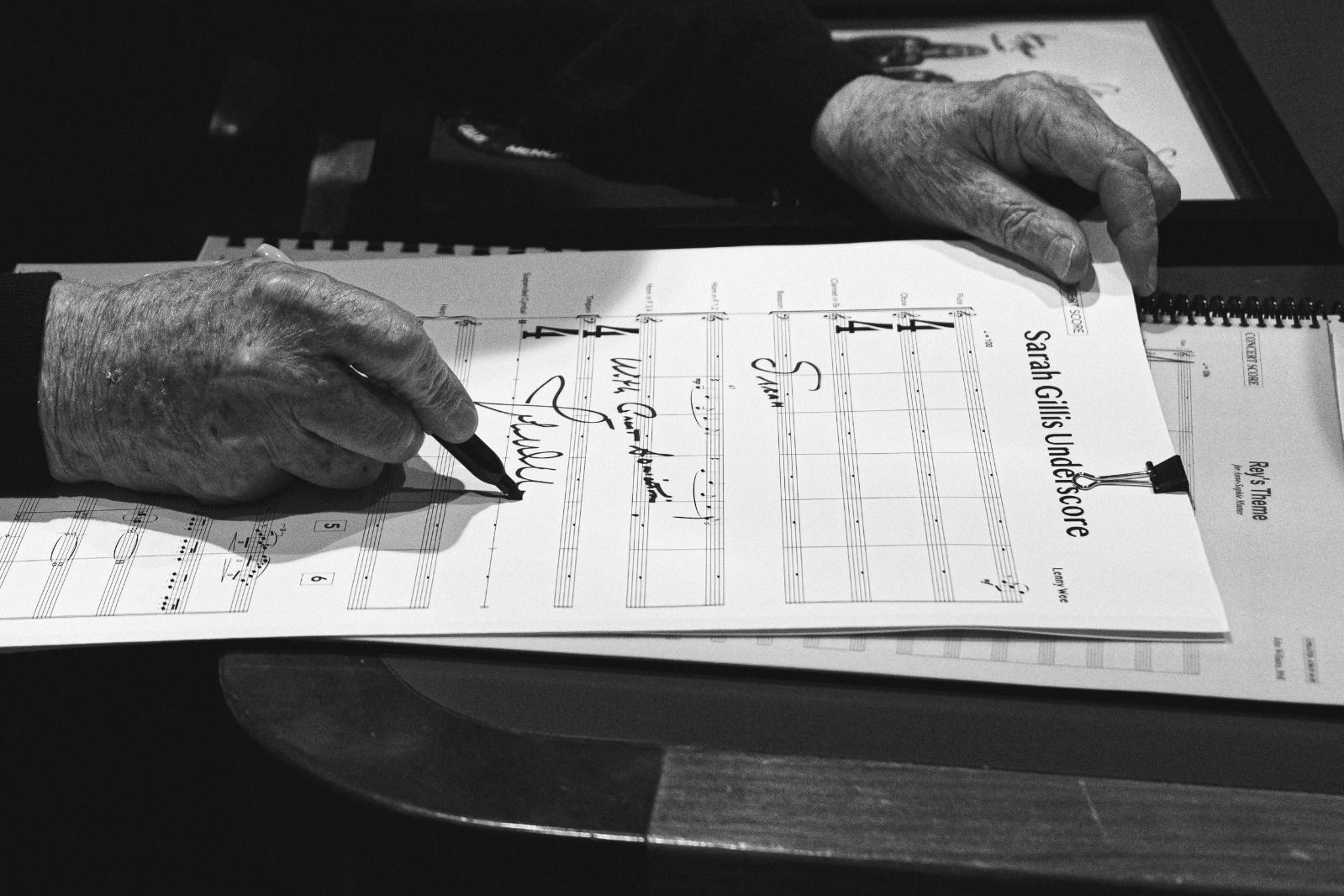

Maestro John Williams signing Sarah’s score.

KE: I understand your crewmates are also John Williams fans. How did they all react to seeing John Williams, or anything you want to mention about that?

SG: I think I maybe underplayed what was happening [with John Williams to them]. I invited my crew to come to this recording session and we had been working on this all in the background. I don’t think they put it all together until they showed up, saw what was going on and realized what all was happening. It was so cool to share the experience with them. They were floored! They were just so excited to meet John Williams. It’s such an immense honor for all of them to get to meet him and sit with him and watch this orchestra get recorded.

I think it’s also one of the moments from the mission that stands out for all of us.

Polaris Dawn astronauts meeting John Williams (l-r: Scott Poteet (Pilot), Jared Isaacman (Mission Commander), Anna Menon (Mission Specialist), Sarah Gillis (Mission Specialist)).

KE: Do you recall when that was in relation to the mission?

SG: It was definitely a number of months ago. I’m in post space brain fog right now, trying to figure out timelines, and I haven’t gone back through in great detail yet, but it was definitely a number of months before the mission. All of the orchestral groups had to be pre-recorded. Given how much our mission was slipping even day by day, coordinating groups to be awake at the same time with all of these slips, was just going to be impossible. These [ensembles] were pre-recorded individually.

KE: How did John Williams’s music influence you both as an artist and personally?

SG: I think, having the opportunity to play his music really makes you want to do it justice. If that makes sense. I don’t think I have ever felt more responsibility to perform something. At least to a caliber that was as high as possible for a spaceflight, considering I didn’t know if it would even work to play a violin in space, how it would sound or if I’d encounter issues that I just couldn’t anticipate. It weighs on you a little bit where you just really want to be able to do justice to this wonderful music, and so I think when I was up there, by the time we were playing, it was just this immense joy pulling out the violin the first time we unboxed it. All the crew had this moment of seeing this wooden violin and a 21st century spacecraft. It was such a beautiful moment, and was the right thing to be doing. We got to play some of the great John Williams’s music in space, which is hard to put into words.

KE: How did you come up with the idea of performing the violin in orbit?

SG: We were trying to figure out what to do for this first transmission over Starlink, and my crew felt I should play the violin. That was the moment we should share with the world. And then it was really just a question of what does that even mean? We had all sorts of ideas, and it took a while to refine them and figure out what exactly that would look like.

But I think it was kind of unanimous really early on that my playing the violin in space is what we wanted to try and do. I think we set the record for the furthest performance from Earth. That might be possible. I actually don’t know. I don’t know if there were any of the higher shuttle missions for Hubble. If anybody performed on those. I’ll have to do some research.

KE: Do you have any memorable stories or moments from your time working with John Williams you can share with us?

SG: I think the whole process for me is just something that’s so outside my everyday experience. You show up to this beautiful soundstage, and there’s a full symphony orchestra getting set up. You feel “I’m the one going to space, but these are the professional musicians in the room”, so I felt extremely out of sorts, stepping into their world and wanting to do it justice, but also not having nearly as much time as I would have wanted to practice ahead of time. I only really found out about it a week ahead of time that we were going to be able to play “Rey’s Theme”.

That’s intense! Horribly intense, and I received the wrong sheet music twice, so I was learning the wrong piece for half that time. I would say that it was extremely stressful to walk in, but I knew this was the recording I was doing just as a backup. If something went wrong in orbit, we would have a backup. I would still have plenty of time to actually get this performance where I wanted it once before I’m in space.

But I actually had this kind of fear that John Williams was going to show up and say, “No!” He would hear me play and be like, “Nope, we’re going to not let you use this music”, but that’s not at all what happened. He was so supportive and gracious. I think his sentiment to us and to the orchestra when he was talking, was one of us is finally going to space, which definitely brought me to tears at the time. But it was representative of his attitude throughout. You know, there is someone that started out as a musician and did not think they were going to ever end up going to space and here they are on this journey and are now bringing music with them. I think that was maybe the most special moment for me to have his support.

KE: Performing the violin in zero gravity must have been challenging and a completely unique experience! What was it like and how did you approach it?

SG: Totally! I had so many thoughts of, “What if this doesn’t even work? What if I can’t get it to sound good, or even play music in the way I need to?” When I first started, I took the violin out and started playing. It was immediately evident that the violin would not stay where I needed it to stay.

In space, when you are shifting on the string, you’re actually pushing the instrument around. I was having to press down with chin onto my shoulder to keep the instrument where I wanted. But even then, it still continued to move, and so the whole time it was kind of this “please, please, please hit the right note, I hope this shift works and the violin doesn’t move to a place that I’m not expecting.” I would say the instrument moving around was maybe one of the biggest surprises. In order to fit the instrument, I was actually playing on a quarter size bow because we didn’t have the space for a bag that would fit a full-length bow, and I didn’t want to come up with a collapsible bow for the mission, so it’s a much smaller sound you can produce with the short bow. I think it also helped, maybe with the physics of it, because it’s already a different bounce when you’re playing staccato or trying to bounce the bow on the string.

It was a little easier to do to begin with the shorter bow. But it was so cool and so funky trying to successfully play and hit the right notes and not have the violin shift.

And then, when we were filming it, my crew members were saying, “I feel you just need to float”, because I was restraining my feet, trying to stay upright and stable, and they’re saying, just see what happens. So, then you introduce this whole added variable of me, moving and running into things, bouncing, and rotating. It was such a joyful, wild, chaotic moment that they were trying to capture. But it was extremely fun to try and do.

KE: Did you do like a dry run before they started filming? Just because I need to see how it feels?

SG: We actually filmed it twice, so I would say my dry run was the first time we filmed it, and we captured footage before the spacewalk, just to make sure if the violin didn’t survive vacuum for some reason we would have some footage. And then after the spacewalk we decided let’s just do a couple more takes. I would say, I did kind of get a dry run with the first performance to the second performance.

KE: Have you received any feedback from John Williams on your space performance of Rey’s Theme? And how has the reception been overall?

SG: Overall, the reception has been extraordinarily positive. I’m actually pretty floored with people’s response to it. Certainly, I hope John Williams enjoyed it, and that I will see him at some point again to talk to him about it in person.

KE: What advice would you give to young musicians, especially those who dream of combining music with other ambitious pursuits like space travel?

SG: I would give them the advice that they should not be limited to one part of their being. I feel so often that people are told they are a musician or an artist or that they are a scientist, and that there’s not a lot of gray area. I really believe that people have immense depth to them, and that they should be bringing all parts of their person and their being to whatever pursuit they undertake. To not be afraid to show up with your full self and your full skills and your full talent because the world needs it.

KE: What’s next for you? Any plans to continue blending music and space or are there other exciting missions and projects for you on the horizon?

SG: You know, right now, I’m in this data processing mode. We have a lot of debriefs that are coming up with the SpaceX team to hopefully bring back a lot of new insights and feedback for improving the Dragon training program and stuff like that. Feedback and data that will help inform design of the next generation space suit. I just don’t know what the future holds yet.

KE: Let’s talk about your work at SpaceX. Can you tell us about your first big career break? How did it change things for you?

SG: That’s an interesting question. I would say my life changed directions very drastically when I met an astronaut for the first time, Joe Tanner, and I was actually in high school at the time. I went with my brother to his college lecture, and he said there was an astronaut coming to talk, and I said, “great, I want to go”. I went with him, and started talking with Joe afterwards. I needed to put together a senior design project for the next year, and I was interested in space. I asked if he might have any contacts I could talk to that might have a project for a high school senior. Kind of an unpaid intern concept. Joe said, “Take my info. I’ll reach out, see if I know anyone.” And he got back to me a couple of weeks later and said, “Nope, nobody’s interested. But I feel like you and I could put together a project pretty easily.”

I ended up working with him for six months. He said, “You should consider studying engineering, I think you’d be really good at it. If you’re interested in coming to Boulder, I’d be interested in writing a letter of recommendation for you for college.” I hadn’t even considered applying for engineering, and I think it was largely out of admiration for Joe that I was willing to look into it. That entirely changed the trajectory of everything I did in life. I went, and I studied [aerospace] engineering instead which was not easy for my brain at first. It was definitely a steep learning curve.

I think through that all having a mentor who was invested in me and invested in my success and when I was ready to quit, was there to say, “How about you get an internship in the industry and see if you actually hate this career, this industry, or if you are just going through stuff in your personal life?” That ended up resulting in an internship at SpaceX. I have been there almost ten years. I interned for two and a half years, and helped develop and test the interior of the Dragon spacecraft, tested on all sorts of our crew members. When it was time to build an astronaut training program, SpaceX said, “you know the interfaces, you helped design them. So now train crews on them.” I was very fortunate to be there at the right time to help build the Astronaut training program from the ground up and somehow that led here. I am immensely grateful for Joe and everything he has done to help shape the course of my life. But I also feel it’s an immense responsibility to help others on that path, because it’s not a journey I would have undertaken without some encouragement, and it’s one that is so worthwhile.

I think that’s where I was motivated to make the music curriculum that I partnered with El Sistema on just how to spark new ideas for kids, and show them what might be possible in different avenues.

KE: What attributes do you feel it takes to be successful at SpaceX?

SG: The SpaceX team is a group of some of the most talented individuals I’ve ever met. Smart, committed, dedicated but I feel what really helps you succeed in that environment is curiosity – if you’re able to approach any situation with genuine curiosity. You don’t need to approach it from a position of already knowing the answer, as if you’re the smartest in the room, but just approach it with open curiosity. Ask questions. Don’t be afraid to ask questions and that’s going to get you everywhere.

People are going to be willing to answer your questions and always want to help. You just need to ask and so I think it’s always the right thing to do to reset to a curious mindset. Nobody hates a puppy. A puppy is going to come up. They’re curious, they’re sniffing around and excited and bringing that joy and curiosity to anything you do will benefit you.

KE: How did you get involved with a Polaris Dawn mission? Did you apply for it?

SG: Jared Isaacman flew on the Inspiration 4 mission and he brought together that crew to be the first all civilian crew to orbit. I had the honor of being their trainer and so after that mission, Jared had been talking with SpaceX about putting together a technology development program. To meet those mission objectives, he wanted to bring together a crew that he thought would be capable of achieving those objectives.

I think in his mind it made a lot of sense that the person who was leading the training program for all the astronauts at SpaceX should know what it is actually like to fly in space and to bring that knowledge back to the SpaceX team. Some random Thursday or Friday, I got pulled into a conference room, and my boss and my boss’s boss were there, and Jared and his team came in and started talking about the program and what it looked like, and then asked if I wanted to fly. It felt extremely surreal!

I think my answer was, “Hell, Yes! But I need to talk to some people first!”, and went right downstairs. My husband works at SpaceX, and so he was at his desk right below us, and I pulled him out and told him, and then had to call my parents and my grandparents!

KE: What was the most surreal, scary, exciting, most memorable memory aboard Polaris Dawn?

SG: There are so many, so many incredible memories from that mission. I do feel like the spacewalk is one of those that’s unforgettable. Where Jared opens the hatch and the entire world is unfolding there and then. We have spent so long – over two years, step by step developing the operation of the SpaceX team working through years of suit design, testing and iteration. It required very precise choreography and just being able to be in that moment with my crew going through that whole sequence that’s definitely a moment that will be with me forever.

KE: Tell us about the countdown and launch experience. What did launch feel like? What was it like in orbit?

SG: The launch countdown was really, really cool. It was actually pretty calm. We ran into “no go” for weather. There was a rain cloud sitting directly above our launch pad at our first T = 0 [launch time].

We actually were sitting on the pad and then performed a T 0 launch time slip. We moved our launch target by about 106 minutes while we were still on top of the rocket. And so, we just sat there and we’re chatting. I think that helped calm down nerves, because you’re just there for a while. And then, as the sequence gets closer and closer, we’re hearing the 10 seconds to launch and then the go for launch.

It’s extraordinarily surreal, because every launch you’ve ever watched, you see the rocket, with fire coming out the [tail] end. You see the clouds of propellant boiling off. You don’t see that in the spacecraft. You’re in this small container. You just get the physical sensations of what those engines are doing to shake the spacecraft.

It was such a cool roller coaster ride up. It’s very smooth on first stage. You start accelerating and accelerating, getting pushed back into your seat until you hit main engine cut off, and then suddenly, you’re thrown forward into your straps, and you’re just kind of hanging there for about 10 seconds before the second stage engine ignites.

Then it ignites and starts pushing you back in your seat and accelerate forward again. And that continues all the way until second engine cut off. And it’s just this building compression. It’s almost like somebody sitting on your chest the whole time. The launch itself was actually not that loud. You’re wearing custom molded ear pieces in your ears that have a microphone into your ear canal, so you’re able to hear clearly and it attenuates the sound. It is certainly loud, but more than that, you experience just the intense sensation of force pushing you into the seat.

And then once you get to second engine cut off, you’re once again thrown forward into your straps, and everything around you is floating, and it’s such a brain glitch to see everything just lift around you. It’s not being held down anymore. You go through this immediate shift of fluid in your body, as gravity is no longer holding all of the blood down in your legs like it does on earth. So, you kind of feel you’re suspended, hanging off a bed upside down by your legs almost where you suddenly have this rush of fullness or kind of puffiness in the face. It’s a fascinating experience just getting to orbit. And then once we’re up there it’s absolutely surreal to float around.

It’s complete freedom of movement. Suddenly you’re in this 3D volume. Instead of just being able to walk across the floor, you can float through any part of the spacecraft with ease. And it’s this total freedom of creativity for how you move and how you interact with the environment. I think that’s what I’ll miss the most is just the ability to float and experience that sensation.

KE: How did the launch experience differ from how you imagined it?

SG: I think I had always tried to envision and put myself in the seat. It was just so much more than I could ever imagine. All of the sensory inputs, the emotions, the entire spacecraft around you shaking. I just could never really imagine the fullness of that sensory experience.

KE: What do you feel most people don’t appreciate enough, or can’t imagine about the experience of going into space and spacewalking?

SG: I think I had always intellectually studied the physical changes you go through when you go to space, like what happens to the human body up there, and I’ve learned about it for years, studied it in school, but actually going through it really drives the point home that in order for people to live for long durations in space flight, there are things we need to know more about. There are problems we need to solve with human health because humans didn’t evolve in that environment. They’re not designed to live without gravity. I would say, we went through all of the things you read about from a physiology perspective in space. And that was extremely eye-opening and a lot of the research that we were doing on this mission, almost forty science and research experiments sprinkled throughout the mission, were aimed at understanding the mechanisms of adaption to microgravity, space motion sickness, some of these things that afflict 50% of astronauts when they get to space. I’m really, really excited to get that data back to the researchers and have them start analyzing it. Hopefully there will be new insights and findings on what could contribute towards making future astronauts’ lives more enjoyable and help future crews be most productive when they are in space.

KE: What went through your mind when it came time for the spacewalk?

SG: So much. I think more than anything that you know we, as a crew, are responsible for each other’s safety and every action we take, every movement we make on this spacewalk could impact all of our safety. I think for me, it was just an immense focus on my crew members what I was doing all of the procedure steps I need to take and really double and triple checking that we hadn’t missed anything, that we hadn’t messed anything up and that we would successfully close the hatch and re-pressurize the spacecraft at the end of it.

KE: Did you or your crewmates experience the “Overview Effect”? (The profound cognitive shift many astronauts describe feeling when seeing the earth in its cosmic context, described as a sense of awe and deepened awareness of humanity’s shared destiny, fragility, and need for global responsibility.)

SG: I think we probably all experienced it in different ways. It’s extraordinary to look down at the earth and see the most beautiful thing you can possibly fathom and know that everyone you’ve ever known and loved is on earth. They’re your friends and your family and everybody you care about is not in space. I think there’s definitely a pull towards people, towards humanity, towards your life down on Earth. It is a life changing perspective that you know our world is incredible and it’s worth fighting for. It’s worth working to improve and change and it’s so spectacular. I definitely am curious to hear my crew members thoughts as well. But it is absolutely beautiful. I think I have barely started reflecting and processing. It’s such an intense experience that I think I will probably be unpacking for years to come.

Out the portal view of Earth from Polaris Dawn.

KE: That’s beautiful. Did you see anything out of out the window that made you wonder what might that have been? UFO/UAP perhaps?

SG: I did not. Unfortunately, I think we did see some satellites which was really cool. We saw beautiful auroras dancing and sparkling this green streak across the earth. But no, no UAPs or UFOs.

KE: Anything you’d like to say about St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital and El Sistema? What do they mean to you?

SG: Part of our mission objective is showing that not only can you make progress for the future of human space flight and drive innovation and technology that will benefit getting more people access to space, but that there are very real problems here on Earth that you can help and support along the way.

St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital is our philanthropic partner in this. The music performance ultimately was a fundraiser. If people want to donate to St. Jude, I would love them to do so, and also equally to raise money for El Sistema USA and the many, many kids they are enabling to have access to high quality music education. Both of those causes are extremely important to me. Our mission is bigger than ourselves, and so whatever we can do to enable those causes is worthwhile.

KE: What did you wish you had known earlier in your life or career? That would have made a difference in your personal journey?

SG: I don’t know if it’s being a woman, I don’t know if it is coming to a different field that was so different than my background, but there were many times that I did not think I belonged in engineering for one reason or another. I think if I had known that I did belong, and I was supposed to be there, and my contributions were equally as valid and as necessary as anybody else’s, that would have helped younger Sarah. You really, really do need diversity of thought and ideas and backgrounds to solve problems in the most effective, efficient, creative way. It takes diversity of thought, of ideas, of people, of background, and that is so extremely important.

KE: Any advice for someone interested in following in your path?

SG: Don’t give up on yourself. Whatever you want to do is possible, and you are going to be your biggest champion, and you absolutely can accomplish whatever you want to.

KE: Would you or your crewmates be open to doing perhaps another, maybe longer, further mission, or is once per lifetime enough?

SG: I think all of us came back from the five days thinking it wasn’t long enough. You’re barely scratching the surface of being productive and experiencing the environment, learning from the environment, capturing the environment. So, while it might just be once in a lifetime, I think if there were more time we could spend up there, we’d all do it.

KE: What about like going to Mars?

SG: Yeah, that’s a good question. I think the engineer in me would want to know a lot more about the mission before I sign up for that, but I think it would be incredible to go and explore another planet – that would be awe-inspiring.

KE: Sarah, have a great afternoon, and thank you again for the time, welcome back home! Thanks so much. Really appreciate it.

SG: You’re so welcome. It’s really great to talk with you today. Thanks for the time.

Polaris Dawn has partnered with St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital and El Sistema USA based on a shared belief in the power of human resilience and pursuit of extraordinary goals. Please consider supporting these two causes in the hope of inspiring the next generation to look towards the stars. Not just to dream, but to overcome, persevere, and achieve the seemingly impossible. Donate now to help build a future where every child has the opportunity to not only survive, but to thrive.

See Sarah’s out of this world performance of John Williams’ Rey’s Theme and support these causes here: https://polarisprogram.com/music/

Details about the Polaris Dawn mission can be found here: https://polarisprogram.com/dawn/

If you’re looking for ways to inspire your students or kids with Space and Music concepts, Sarah’s “Astronaut’s Guide to Reaching for the Stars” can be found here: https://polarisdawn.elsistemausa.org/. The “Bonus Zone” explores some of the musical elements in Rey’s Theme.”